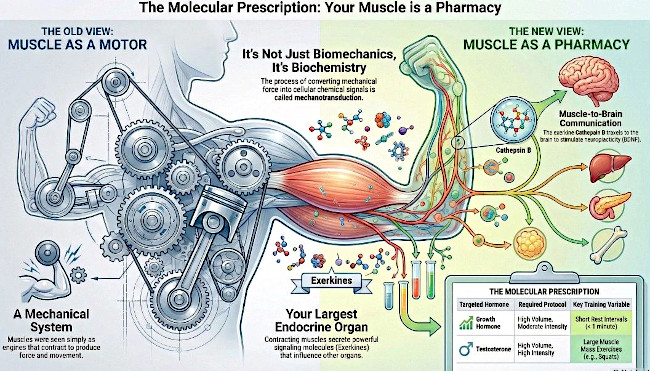

Soon after I finished writing last week’s blog, I bumped into another great post and infographic titled “Your muscle as Pharmacy”. In the text the author, M Vedith, discusses the role of muscles as an endocrine organ, using exerkines to signal our organs, continuing the discussion on the benefits of exercise that we have been sharing.

The author shared an infographic (below) and invited everyone to discuss the way we explain the systemic benefits or strength training and muscle.

Fig 1. Your muscle is a pharmacy (M Vedith, 2025)

I like this image as it quickly leads us from the old to the new thinking. While the old view only saw muscles as a motor for movement, we now understand that we cannot just talk about biomechanics, rather we should talk about biochemistry.

For a long time we have been talking about Exercise as medicine, and the global pandemic really brought forward the impact of exercise is preserving health. In 2020 we started our webinar series where we invited guests to talk about their expert topics. In 2022 two specialists joined us in our webinar titled Exercise is Medicine. In this episode Brad McGregor and Sam Waley discussed how their knowledge led them to run facilities where exercise is the key medicine. As Sam’s business partner Nick Kokotis, MD stated in an earlier Newsletter article – Exercise is the Answer, now ask me the question.

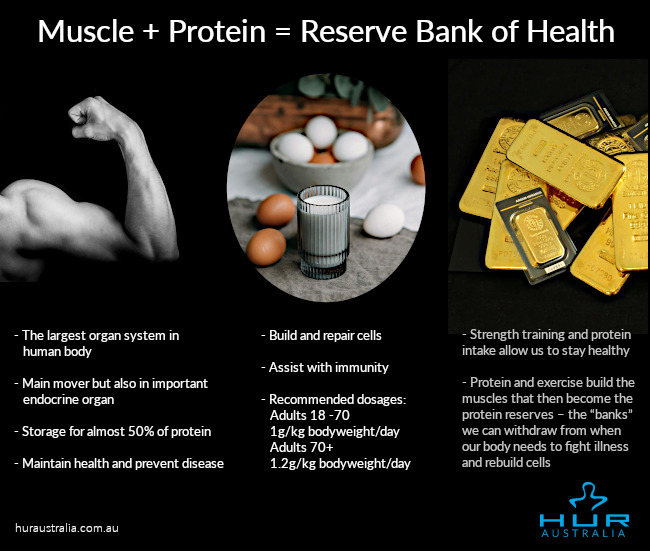

I have quite a few idioms that I use when discussing the benefits of exercise, trying to liaise the benefits to other contents, sometimes more familiar and understandable.

I often call muscles, together with protein intake, our Reserve Bank of Health. Skeletal muscle is the largest organ system in our body, second to water itself. Whilst our muscles are our main movers, they also have a role as endocrine organs with many responsibilities in the management of general health.

There is overwhelming evidence from research over the past decades highlighting the importance of strength training to optimise muscle mass, strength and function, and its importance to maintain health and prevent disease. Muscles have a direct liaison to many functions beyond locomotion, such as metabolic rate, glucose metabolism, cognition, blood pressure, and blood lipid levels.

Indeed, muscle mass and strength has been directly linked to the treatment and prevention of almost all chronic diseases, and when exercise is properly prescribed, it can work as an efficient medicine to optimise muscle health and reduce the risk of many conditions. Skeletal muscle is the largest organ system in our body, second to water itself.

Furthermore, skeletal muscle makes up almost half of the protein reserves in the human body. Proteins are the main structural components of cells with the responsibility for many physiological tasks such as building and repairing cells including muscle tissue and assisting in the fight against any viral and bacterial infections.

Muscles behave as our protein reserves – the “banks” we can withdraw from when our body needs to fight viruses and rebuild cells. Understanding that muscles could act as an immune organ by producing acute phase protective proteins, regular strength training might be a crucial preventive action to fight against diseases.

Muscle health matters. As the average person can lose around 30-40% of their muscle mass from between 20 and 80 years, it is time to get into action and preserve the strength we have, despite the age. The many functions of muscle are well explained in our webinar from 2021 “Muscles and mobility matter: lessons from research to inform practice” again had world class speakers – Professor Robin Daly, a Deakin University Researcher with a long research profile on Sarcopenia, and Richelle Street, from Blue Care, and exercise physiologist with a passion for health and wellness, especially in older adults.

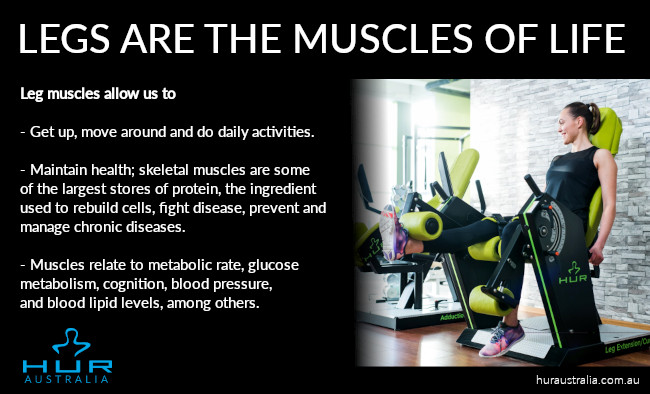

Another saying that relates to this: Leg muscles are the muscles of life.

Leg muscles are the muscles of life; They allow us to get up, move around and do daily activities. They also play an important role in maintaining health; skeletal muscles are some of the largest stores of protein, the ingredient that we need to rebuild cells, fight disease, and play an important role in the prevention and management of chronic diseases.

Leg muscles (such as quadriceps, hamstrings, and gluteal muscles) are used for major movements such as standing, walking, getting up, squatting/crouching down and running, among others.

The ability to complete these activities equals to independence and quality of life for many, thus the loss of the leg strength can be a significant event.

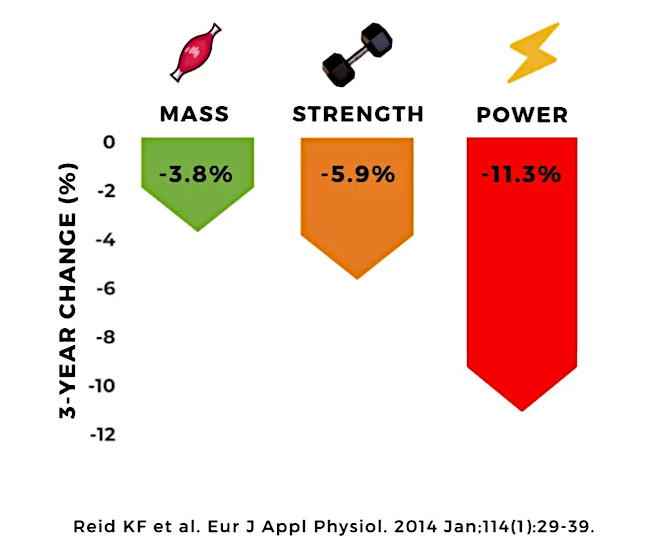

The loss of muscle mass and strength are often observed, but less attention is paid to muscle power, the ability to produce force quickly, such as the ability to move your foot quicky at the loss of balance or walking up stairs.

It has been shown that muscle power declines earlier (around the age of 35-40) and more rapidly (with up to a 50% loss with age) than muscle mass or strength.

Image by Fyfe J. (2023)

The loss of muscle power is significant as it relates directly to functional limitations and disability. To preserve muscle power, exercise routine must include high speed resistance training, in which you perform the lifting phase of lower limb exercises as rapidly as possible.

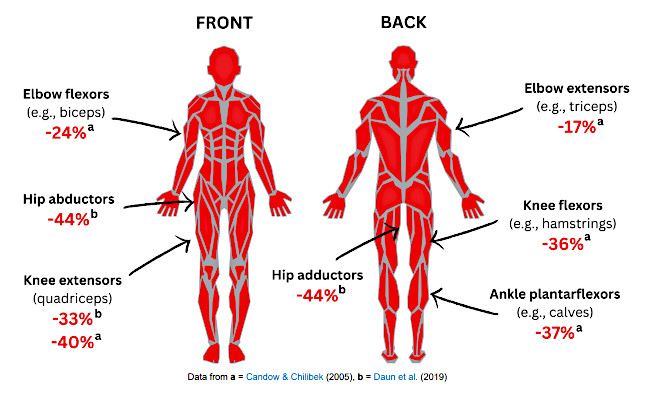

Whilst we have acknowledged the importance the leg muscles for health, it is also important to note that muscle loss is not equal, rather we lose these important muscles faster than the rest, as wonderfully summarised in this image below by Jackson Fyfe (2025).

Upper-body muscles, eg. biceps and triceps, lose about 15–25% of their strength with age whilst Lower-body and hip muscles, eg. quadriceps, hamstrings, glutes, and hip stabilisers, lose 35–45% or more. Our lower-body muscles, our muscles of life, lose roughly twice as much strength as many upper-body muscles over time.

Image by Fyfe J. (2024)

Back to the idioms – I like also to talk about the comparison between health and wealth. We know that we need to take care of our finances, therefore we pay attention to our income and spending.

What if we thought of exercise as we think of money?

Many people had a “piggy bank” at young age. The purpose of these was to teach us to save money, often towards a goal. This was easily done – If we consider this in exercise terms the basic exercise – we move but consider that any exercise is good exercise, and eat generally healthy food, without any additional emphasis on nutrients that boost our health more than others.

From the piggy bank saving the next step was to open a bank account – it was exciting to go to the bank and get the secret number to store our funds, and maybe even see the savings grow. In exercise terms, we could call this the stage when we start taking exercise a bit more seriously.

We start considering strength training, maybe even join a gym. We start to understand the different aspects of exercise, and the benefits they may give. We also start paying attention to nutrition and have a better focus on the ingredients that matter the most to our health.

To save money for retirement and older age we all are saving in a super fund, and many invest in funds and in stock market, hoping to maximise the growth of our income. When investing in stock market there will be dips, but as we grow the base funds, we can afford these occasional decreases I the funds, and as the market gets better, we know that the funds will grow to the earlier level, and beyond.

In exercise terms, this is us getting serious with our exercise; this is when we realise that exercise and strength training are the best investment we can do to maintain our health.

We start training at a gym with appropriately prescribed, progressive strength training program, and have an appropriate protein intake. As our strength levels increase, we can have that “dip” in our strength due to inactivity, or illness, as the buffer that we have gained keeps up in a strength level where we can return to training program as allowed.

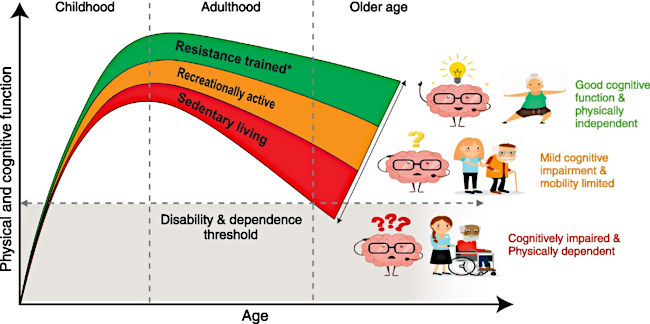

In the last few years research articles have also provided fantastic graphics that summarise the reasons so well.

Effects of (in)activity and resistance training on physical and cognitive function across the lifespan. Abou Sawan, S; Nunes, Everson A.; Lim, Cn McKendry, J Phillips, S M. Exercise, Sport, and Movement1(1):e00001, January 2023

This is why we must exercise – we want to keep a good cognitive function and remain physically independent. We want to choose the path that allows us to maximise our healthspan and live a life where we add life to our years, not just years to our life.

More than a decade ago the Canadian Heart & Stroke Foundation published one of the best videos that really show the difference our choices and action do. The video asks – what will your last ten years look like? Will you be healthy enough to play with your grandchildren, strong enough to embrace every moment.

Will you grow old with vitality or get old with disease?

The images, diagrams and videos aid us in telling the story, in sharing our mission. In the end we hope to empower everyone to make exercise a priority that allows us to live a long life with health, happiness, independence and great quality of life.

Best wishes,

Dr Tuire Karaharju-Huisman

Physiotherapist, Accredited Exercise Physiologist (ESSAM), PhD (Biomechanics)

Research Lead, Area Account Manager (Vic, Tas, SA, NT, WA, ACT)